Health

Alzheimer’s disease: Presentation, Symptoms, Pathology, and Diagnosis

|

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and, eventually, the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. In most people with Alzheimer’s, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s.

Alzheimer’s disease is currently ranked as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, but recent data indicate that the disorder may rank third, just behind cardiovascular disease and cancer, as a cause of death for older people.

We’re going to look at the presentation of Alzheimer’s disease and the different symptoms that people affected by it can manifest. We will see that there are different ways in which Alzheimer’s disease can manifest itself. It could be a memory syndrome, visual syndrome, language syndrome, or frontal lobe syndrome. We will dive a little bit into neuropathology to discuss the findings in the brains of people who had Alzheimer’s. We’ll also look at some of the disease’s genetic factors and then finish by taking a look at some of the modern biomarkers and techniques to test for this disease.

There’s a gradual progression of Alzheimer’s disease where it starts affecting the brain way before we can actually detect any sign. This is the asymptomatic phase of Alzheimer’s disease. Then symptoms may start showing up in people’s thinking, memory behavior, etc but these could be mild. Or these symptoms could be more progressed and cause people to be dependent on others for their well-being in their day-to-day life. We call that dementia.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), is described as a clinical state where a person has a cognitive or behavioral decline of any cause that does not significantly interfere with independent living. These are people who maybe forget things but can continue to take care of themselves. They remember to take their medications, can shop and cook and pay bills and take care of their hygiene, etc.

As opposed to this, the term dementia describes a clinical state where we do have cognitive or behavioral decline, again of any cause, but this time, it does significantly interfere with a person’s independence in completing their day-to-day function. They become progressively more reliant on family, loved ones, or hired caregivers in order to provide different levels of care that they need.

It’s important to understand that not every person who has dementia or MCI necessarily has Alzheimer’s disease. Both these terms MCI and dementia are just clinical terms and a lot of things can cause them. Also, not every person with mild cognitive impairment necessarily will progress to have dementia. We have all of the possibilities.

A person can be clinically asymptomatic, they can have mild cognitive impairment or they can have dementia. One may progress to the other but not necessarily.

Let us look first at the clinical syndromes, which means the way that the disease manifests itself in humans. There are four most common syndromes.

1. Amnestic syndrome

The first one, the memory/ amnestic syndrome is probably the one that is considered the most typical or classical Alzheimer’s disease manifestation. When people in the community say Alzheimer’s disease, usually this is what they think of. They think of memory loss.

The first sign usually is a sign of short-term memory loss, meaning that they start forgetting things that happened recently, not long ago, last week, three weeks ago, this morning. As the disease progress, that time delay might become shorter and shorter, where they might forget a conversation that just happened an hour ago or something that someone said 10 minutes ago. Typically, the memories for things that occurred a long time ago remain preserved sometimes to even at a later stage of the disease.

However, we do know that the past can start marching backward in the sense that people start recalling more vividly things progressively from an earlier period of their times. In fact, some patients, when they progress, might start recalling very vivid memories from when they were at school or children, etc. The way that it manifests itself is that people may forget events that they went to, they may forget conversations, they may repeat stories, tell you something that they have already just told you, or that they told you three days ago. They can misplace their belongings because they forget where they put something down and they go to look for it.

Over time, other symptoms might arise that are not necessarily related to memory. They might start having difficulty navigating and getting lost. This is a combination of not recalling where things are in their internal map, but also having some visual problems. It can also progress to include language difficulties, forgetting words that they used to be able to say.

It may affect behavior. Some people may become anxious, other people might become more detached. Late in the disease, other cognitive domains might be affected as well, such as exact functions, problem-solving, etc. When the classical or typical Alzheimer’s disease occurs, we believe that the memory is happening because the disease is affecting a very particular part of the brain called the hippocampus.

The word hippocampus is named after a seahorse because it looks so much like a seahorse. The word hippocampus is a seahorse in Greek. On an MRI of a patient that doesn’t have Alzheimer’s the hippocampus is quite big and bulky. In patients who have Alzheimer’s disease, the hippocampus might really lose a lot of volume, because brain cells are dying as time goes by, and so instead of having that sort of really nice and plump hippocampus, you might have a space in the place where it’s supposed to be. In some patients, you may not even see a hippocampus any longer. This is in summary the presentation of somebody with a primary memory problem.

2. Posterior Cortical Atrophy syndrome

Now people with Alzheimer’s disease may also present with primary difficulties in visual processing, not necessarily affecting their memory. This is a syndrome that is currently known as posterior cortical atrophy. Some people refer to it as the posterior variant of Alzheimer’s disease.

In these people, the disease usually presents earlier for reasons we don’t understand. They are younger, maybe in their early 60s or late 50s. The first sign and symptom of this is impairment and visual processing. They start having difficulty locating things in space. They may open a fridge to look for eggs, and because there are a lot of things in the fridge, they’re not able to visually process where the eggs are located in the fridge.

They may have difficulty with the sizes of things. They may go to fetch a big glass or mug and they fetch a smaller one instead or have difficulty with the placement of cutlery on the table.

They also have difficulty navigating their own space. A room would be very difficult to navigate for somebody with this type of Alzheimer’s disease. Because to be able to go through they may have difficulty locating the door and on which side they have to go, and how do they avoid bumping into people. It’s very difficult.

They may also have difficulty recognizing faces or objects. These patients may earlier in the course of the disease, have difficulty recognizing family members or famous people on television. Over time the disease may progress to then include memory problems and then it can, later on, start to look like the amnestic form of Alzheimer’s disease.

But most of the time in the first 2 or 3 years, it’s primarily a visual problem for these patients. These patients are the most likely to have an insight into their disease, which means out of all the people with Alzheimer’s disease, they are the ones that recognize the most that there is a problem going on and that they are unable to manage their space. Some people believe that because of these visual problems, but also may be other factors related to where the illness is attacking, they may be very depressed or very anxious.

If you ask a patient with the visual form of Alzheimer’s to describe a busy picture, you notice that they describe only a part of the picture and completely omit the rest. This is one way in which we can test this syndrome. In people with this type of disease, it affects a very different part of the brain, which is the posterior part of the brain. This is a part of the brain that’s called the parietal lobe and is responsible for a lot of our visual processing, but also some other things like math and calculation. It plays a role in language and also a sensory role – how we feel things, etc.

On an MRI of the brain of such a patient, there is volume loss in the back part of the brain, whereas the remaining brain looks more or less okay. The hippocampus in these patients is relatively slightly plumper than what we expect for somebody with Alzheimer’s disease. So the main problem is here in the posterior part of the brain.

3. Logopenic variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia

The language syndrome, what is referred to as the logopenic variant of Alzheimer’s disease is a third way in which Alzheimer’s disease can present itself. It also tends to occur mostly in younger people. The first sign is a language difficulty and specifically, people have a really hard time coming up with words and spontaneous speech. They would be talking and then all of a sudden they blank on a word. They may try to talk around it. Like if they were to say a hanger, they might say ‘the thing that goes in the closet and you put your clothes on it’. They blank on the word and say all these things around the word.

The exact process that is being impaired in these patients is that they have a really hard time with anything that comprises the sounds of language. Languages are a very abstract concept. Who decided that if I say the sound “Bark”, that means something to us. That the “bark” is the sound that a dog makes. Or if I say something that is merely a sound with no meaning as we know it, that that’s nothing. It doesn’t mean anything, but that’s still a sound. It’s a very abstract concept we have learned since we were young that these particular sounds are associated with a particular meaning or concept.

There’s a part in our brain that is responsible at all times to sift through all the sounds that you get from your environment and allow you to differentiate between ambient sound and language sounds and then once you are able to process all of that, you then attach the meaning to each of the sounds and that’s how language even starts to be processed in the brain. There are other parts of the brain that sort of take over for you to add the richness and texture of what it is that you are being told, how you’re going to respond to it, etc.

That initial process of understanding the sounds of language is what’s being affected in these patients. That’s why they start blanking on words because they can’t hear them, they cannot hear what they sound like and also they start having difficulty listening to people talk, especially if they are being told something that’s really long because it’s way more sounds. If I were to tell you, “Come here,” these are two sounds, two syllables. It’s way easier to process than if I say, “Make sure you are here by 2 pm tomorrow. We’re going to a show. It starts at 3 pm.” These are a lot of sounds that the brain now has to process.

People who have this variant of Alzheimer’s disease will have a really hard time with these longer sentences as opposed to shorter sentences. As the disease progresses, they may have more and more difficulty with language so communication might be really impaired. Some patients do become sort of close to mute or are unable to really provide any meaningful conversation.

Early on it might also affect calculation faculty because we’re going to see that this is the part of the brain that’s close to where we process sounds of language. They may then start developing more visual problems similar to the group that we discussed right before this one.

These patients probably also have a lot of memory problems that might be hard to detect. Because if you cannot speak, you may not have an opportunity to know that you forgot something because it may not come up in a conversation.

This is a test that we give to these patients in order to see how they’re processing the sounds of language. The test is really simple. We ask them to repeat a sentence and repeating a sentence does not require you to really understand it. All that it requires you to do is to be able to process the sounds of that sentence and reproduce these sounds. People may not be able to understand what they’re saying, but they may still be able to repeat it. However, people with this variant of Alzheimer’s disease have a really hard time.

What’s interesting, and if you notice, there will be some errors in the words that they say. These words may sound like what you’re saying but they will not be the right words. e.g. The patient may say winter as opposed to a snowy day. This is an error that often these patients make because as they are searching for the sounds, other sounds are being grasped in the brain and they’re going there.

The part of the brain affected in these patients is part of the parietal lobe but it’s a little bit lower. It is where we process some of these sounds of language. This is the reason why these patients struggle.

4. Frontal variant of Alzheimer’s Disease

The fourth variant is the executive syndrome or the frontal syndrome. This is a variant that also occurs at an earlier age and affects the frontal lobe of the brain. The frontal lobe of the brain is responsible for a lot of really important day-to-day things. It is making decisions, allowing us to know what we want to do today, plan our day, execute that plan, motivate us in order to go ahead with our plan.

When the frontal lobe is affected by Alzheimer’s disease, and then people start losing this capacity and they might start having difficulty with problem-solving. Maybe they tended to their garden and knew how to organize it and now stop doing that. For a lot of people, it can show up at work. Remember these are people that could be younger, in their 50s. Often they are still working and they may start making errors or have problems with making decisions at work.

The frontal part of the brain, in addition to being the decision-maker and the executive processor, is also the part of the brain that is helping us select the best behavior in any particular social setting that we are in. If you think about social situations, you could be in a very professional situation or in a family situation, or you could be out with friends having drinks. If the same scenario or the same conversation happens in each one of these situations, you might respond differently because you’re in a different space.

Maybe you’re having fun at night with your friends, but with your boss, you have to take things seriously. The frontal part of the brain is what is allowing us to process all the time what’s coming at us from the environment and have the ability to select what is the best way to behave right now given the setting that you’re in.

Patients may start having difficulty knowing what to do from a social perspective. A lot of them become either inappropriate in social settings or disinhibited. Again, over time this condition progresses to involve also other cognitive domains like memory, language, and vision, as we saw previously.

Pathology of Alzheimer’s disease

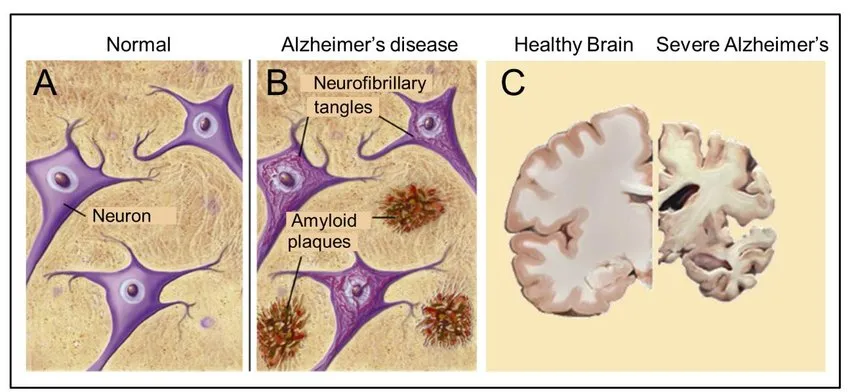

Now let’s look at what is happening inside the brain and take a dive into the pathology. The hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease is the presence of two main findings. One is called senile plaques made of beta-amyloid (Aβ), and the other is called neurofibrillary tangles that are made of a protein called tau.

On our brain cells, we all have this molecule called the amyloid precursor protein. We’re not quite sure what the amyloid precursor protein does. But we know that when it is snipped in ways to form beta-amyloid, these beta-amyloid can aggregate together and form a senile plaque. The senile plaque can come in two forms – either as diffuse Aβ plaques or as neuritic plaques. Both of these are outside a brain cell.

Then there’s another part of Alzheimer’s disease which is related to another protein called tau. Tau is a protein that is usually part of the architecture of a cell. Any cell in our body and specifically our brain cells are made of a skeleton. That skeleton that holds the cell together is made of proteins that are called tau protein. They come together in order to make microtubules that form the skeleton of the cell.

However, at times when something is going wrong inside the cells, the tau proteins may become hyperphosphorylated. Meaning they have too much phosphorus attached to them and they are unable to form nice microtubules. Instead, they aggregate together and form neurofibrillary tangles.

These are actually inside a brain cell because the tau protein is supposed to be inside to form the skeleton. When it’s unable to do that, it aggregates inside the cell and contributes to damage causing brain cells to die as time goes by.

Alzheimer’s disease is the term that we use to describe the specific neurodegenerative disease of the brain that is associated with progressive accumulation of these amyloid plaques and tau tangles that over time they lead to irreversible degeneration of neurons, meaning that neurons die as time goes by.

There are different ways in which we can stage Alzheimer’s disease from a pathology perspective. Let me actually start with the beta-amyloid staging. We had talked about these two different types of amyloid – diffuse deposits, and neuritic plaques. There are two different ways in which pathologists look at a brain and decide as to how much amyloid plaque there is or what is the distribution of it.

The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD) developed a neuritic plaque scoring system, which ranks the density of neuritic plaques identified by Bielschowski silver stains in the neocortex. We can quantify the amount of Aβ by looking at the neuritic plaques and see how dense they are on microscope slides.

The Thal system describes 5 phases of Aβ deposition. In phase 1, only the neocortex is affected. Progressively, amyloid spreads to the allocortex, subcortical nuclei, brainstem, and, in phase 5, it involves also the cerebellum. Phases 1-5 informs us about where in the brain these amyloid plaques are being found. These are two ways in which we quantify the amyloid presence in the brain. This is all on autopsy.

Occasionally, very rarely patients get a biopsy of their brain because people aren’t quite sure what’s going on and they think this might be a good diagnostic way. So we sometimes find that on biopsy, but most of this is on autopsy.

Regarding the tau staging, tau seems to have a much more predictable way in which it spreads in the brain, and it seems to always start close to the hippocampus and this region called the transentorhinal region of the temporal lobe. It starts spreading from there to the hippocampus. Then involves more of the hippocampus and the temporal lobe. Then as it spreads more to the cortex and involves different cortices, it becomes more and more widespread in the brain.

Each one of these has a stage that was first described by Braak and Braak, and so we call this a Braak staging of Alzheimer’s disease. The higher the Braak staging in the brain, the more diffuse the tau tangles are, and usually this correlates with the severity of the symptoms. So the more tau you have, the more symptoms you have but the accumulation of amyloid does not always necessarily correlate with the severity of the symptoms.

Unfortunately, we have not yet scientifically found how we can stop this disease from spreading, and we do not currently have medications that have been shown to prevent its progression.

There are several experimental medications, some of which have been tested for the past decade to try and clear the amyloid plaques from the brain. So far we have gotten unfavorable results. In some patients, the amyloid plaque was seen to be removed, but that wasn’t paralleled by an improvement in disease or stopping of the progression. There may be other factors that we still don’t understand or know about this. There are other current medications also that are trying to clear the tau tangle from the cells and see if we can stop its formation. But this is also still under experimentation.

We’re hoping that as we learn more and more about the biology of this and how it spreads from cell to cell and how it forms in the first place, we’ll be able to have more targeted medications to try and halt this process or even reverse it if we can.

Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is actually rarely caused by a single gene variant. Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease accounts for the majority of the cases, approximately 75% of people. Sporadic means that they presented to us with no family history of Alzheimer’s disease whatsoever.

Familial Alzheimer’s disease is when we know for certain that it is linked to genes. This is also defined as people who have two or three relatives with Alzheimer’s disease. In families that are affected, members of at least 2 or 3 generations are affected. But they all don’t necessarily have a dominant gene. They account for around 25% of cases.

Familial Alzheimer’s disease can be further divided into – Early-onset familial disease and late-onset familial disease. Early-onset familial disease is caused by mutations in the presenilin 1(PSN1), amyloid precursor protein (APP), and presenilin 2 (PSN2) genes. It is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner and accounts for about 5% of cases of familial Alzheimer’s disease.

In late-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease, mutations are present in the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene.

All of us have 23 pairs of chromosomes in every cell of our body. These chromosomes really contain in them the entire codes of who we are. It is genetics that dictates everything about us. Every cell in our body expresses sometimes different parts of these 23 chromosomes. Expressing different parts of the genetic code enables cells to become different cells in the body.

Presenilin 1(PSN1) is on chromosome 14. When patients have a mutation in PSN1, they can present with Alzheimer’s disease at a fairly young age. Usually, the onset is between the age of 25 and 60, with the average age around the age of 14. The symptoms can be quite different than what we just talked about. It’s not just memory problems, but people can have Parkinson-like movement problems, ataxia, which means incoordination in their movement. They can have behavioral changes. The mutation causes the buildup of beta-amyloid in their brain cells, and this is what causes the disease.

There are a few founder variants, meaning that these are the places in the world where we have found families that have this gene. It’s really in very specific parts of the world that this gene is present.

The presenilin 2 (PSN2) is extremely rare. So the majority of cases are PSN1 or APP. PSN2 mutation is extremely rare and it is present on chromosome 1. The onset is young between 40-75 years of age with a mean of 50, and it mostly occurs in people of German, Italian, and Spanish descent. It leads to a build-up of amyloid protein.

The amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is the second most common gene, is on chromosome 21. This the same chromosome that is affected in people with Down syndrome who have trisomy 21. In Down syndrome, you’ll have 3 copies of that chromosome instead of the regular two that all of us have. Because of the 3 copies, people with Down syndrome are at a very high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, people with trisomy 21, the majority of them, if not all of them, if they live long enough, will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Again, this is caused by a buildup of beta-amyloid as well.

Apolipoprotein E

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) is the major cholesterol carrier in the brain, affecting various normal cellular processes including neuronal growth, repair and remodeling of membranes, synaptogenesis, clearance, and degradation of amyloid β (Aβ), and neuroinflammation.

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a gene that has three major different forms – E2, E3, and E4. You have two copies of APOE because we all have a pair of chromosomes. You can have two of any of these three forms – E2, E3, and E4.

E2 is considered to be protective against Alzheimer’s disease. E3 is considered to be neutral, it doesn’t necessarily do anything, and E4 is considered to confer risk on patients who have it to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

None of these is causative. You do not need APOE4 to have Alzheimer’s disease and also having APOE4 does not mean that you will develop Alzheimer’s disease. So this is not a cause, it just increases the likelihood or the risk that you may develop it given other factors. Having E4 may mean that you develop Alzheimer’s disease earlier in life than people who don’t have the APOE4.

In general, one E4 copy is associated with an 18-35% lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Two E4 copies are associated with 31-40% of the lifetime risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Other contributing factors in Alzheimer’s disease

The role of the environment, diet, and general health in Alzheimer’s is being actively explored. Chronic cellular damage from free radicals, non-enzymatic glycation of proteins, and other factors contributes to the loss of neurons and synapses that is associated with old age and aggravates the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease.

Neuroinflammation, free radical damage, type 2 diabetes, traumatic brain injury, and increased homocysteine levels are some factors that are emerging as factors involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease.

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

We have biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease, which are like proof of evidence. Having a biomarker that is “positive” increases the certainty that whatever syndrome you’re seeing, is due to Alzheimer’s disease. So we know that the memory problem or the visual problem, or the language problem is indeed being caused by Alzheimer’s disease.

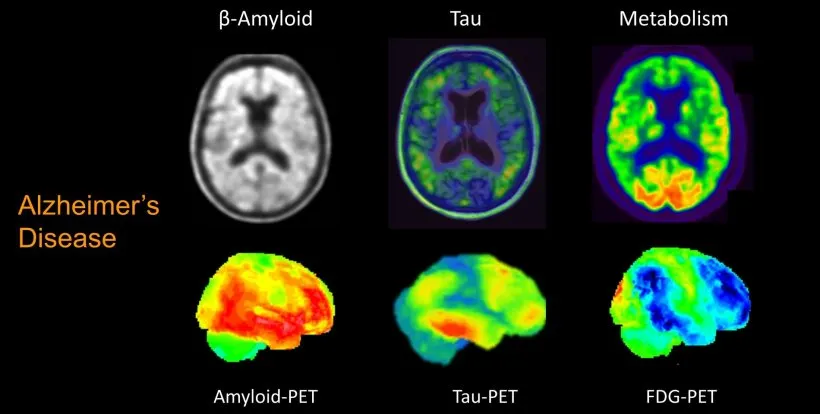

Biomarkers fall into three categories. There are biomarkers for amyloid deposition, where we can detect whether there is amyloid pathology. One is measuring the amyloid protein levels in the fluid that is around the brain and our spine i.e. the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

At all times our brain and our spinal cord are actually floating inside a cavity that is filled with fluid. This fluid is called cerebrospinal fluid. We can test the CSF for amyloid markers.

Another technique for amyloid is doing a PET scan. A PET scan checks whether there are amyloid plaques or amyloid depositions in the brain.

The second biomarker, which is really promising, is a PET scan for tau protein. A PET scan allows us to see tau depositions in the brains of people who have Alzheimer’s disease.

Then the third type of biomarker is really a biomarker of neuronal injury. This means that it may not necessarily be specific to Alzheimer’s disease in the sense that it’s not showing us the amyloid plaques or evidence for that or the neurofibrillary tangles, but it is telling us that brain cells are dying. We can see this again in CSF.

Once we get the CSF, we send it to the lab and it comes back with a report where they show us the levels of the amyloid protein in the CSF and the top protein in that fluid. Now, this may not make a lot of sense, but if the amyloid protein is low in the CSF fluid, this is the marker for Alzheimer’s disease.

We don’t quite understand the biology of Alzheimer’s too well. But the way to make sense of it is that if the amyloid is forming the plaque, not enough of it is circulating in the fluid to detect it. If the amyloid level is low, then this is a biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease.

If the tau level is high, this is a biomarker of neuronal loss. It’s not a biomarker of tau deposition necessarily. It doesn’t necessarily tell you that there are tau tangles in the brain, but it tells you that brain cells are dying. As they’re dying, they are exploding and releasing all that tau protein in the CSF. This is what we are picking up.

Other advantages of doing a spinal tap or a lumbar puncture are that we can also measure for other things that sometimes may be causing memory problems and aren’t Alzheimer’s disease, like inflammation in the brain, infections in the brain, tumors, lymphomas, etc. Getting a sample of the CSF allows us to test for other things that aren’t Alzheimer’s disease, and that’s always nice and it complements the work-up.

Did you find my article “Alzheimer’s disease: Presentation, Symptoms, Pathology, and Diagnosis” helpful, or know somebody who would? I’d really love it if you could share it.